by Ben Murray

Dukes Education Group Ltd

There’s something about winter that makes stories feel extra magical. Perhaps it’s the early darkness inviting us to gather closer, the hush of snow (or just frosty mornings) creating a sense of wonder, or the way our senses come alive in the crisp air. In Early Years settings, winter storytelling can be an enchanting way to spark imagination, explore language and connect children with both tradition and the natural world.

When we weave together seasonal tales, cultural folklore, sensory props and a dash of drama, we create experiences that children carry with them long after the snow has melted.

Winter is rich in imagery and emotion. There are twinkling lights, swirling winds and tales of journeys through snow. It’s a season full of contrasts: cold outside, warmth inside; bare trees, but hidden seeds waiting for spring. This provides a perfect backdrop for stories that nurture language and imagination.

For young children, the sensory richness of winter – the crunch of ice, the sparkle of frost, the smell of cinnamon – helps anchor storytelling in real, tangible experiences. This sensory link not only makes stories more vivid but also strengthens memory and comprehension.

When selecting winter stories for the Early Years, it’s important to match language complexity, themes and illustrations to the age and stage of the children. Here are some age-appropriate winter favourites:

For two to three year olds:

Snow Bears by Martin Waddell – Gentle, repetitive text and warm illustrations of animal friends exploring the snow.

Owl Moon by Jane Yolen – Poetic, atmospheric, and perfect for introducing descriptive winter language.

One Snowy Night by Nick Butterworth – A comforting tale of sharing warmth on a snowy night.

For three to five year olds:

The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats – A classic that captures the quiet joy of a snowy adventure.

Winter Sleep: A Hibernation Story by Sean Taylor & Alex Morss – Combines narrative with factual elements about winter wildlife.

The Mitten by Jan Brett – A traditional Ukrainian tale of animals sharing shelter, with rich opportunities for prediction and sequencing.

Winter storytelling is a beautiful opportunity to celebrate cultural diversity. From Norse myths of frost giants to Japanese folktales of snow spirits, winter stories are found in every culture.

Consider exploring

Scandinavian: Stories of the mischievous Tomte, a small gnome-like figure who helps around the farm in winter.

Eastern European: Variations of The Mitten and other shelter-sharing tales.

Japanese: Yuki-onna, the snow woman – a gentle, adapted version for young listeners, focusing on snow magic rather than fear.

Indigenous North American: Legends explaining how animals survive winter, such as how the rabbit got its white coat.

When sharing cultural tales, ensure they’re told respectfully and accurately and adapt language for age appropriateness while keeping the spirit of the story. Where possible, include visual elements like traditional clothing, patterns, or snowy landscapes from the culture’s region.

Children learn best when they’re actively engaged. Interactive storytelling turns listeners into participants, making the experience memorable and joyful.

Use sounds

• Crunching footsteps in ‘snow’ – scrunch tissue paper or walk on salt in a tray.

• Whooshing wind – soft whistling or shaking a rain stick.

• Animal calls – owls hooting, wolves howling, reindeer bells jingling.

Add movement

• Encourage children to stomp like polar bears, tiptoe like foxes, or sway like snowy branches in the wind.

• Use scarves or pieces of fabric to ‘catch snowflakes’ or create swirling snowstorms.

Bring in drama

• Invite children to take on roles – the bear in a den, the child lost in the snow or the robin searching for berries.

• Use props like lanterns, mittens or soft toy animals to bring the narrative into the physical space.

These techniques make stories multi-sensory, supporting different learning styles and helping even the youngest children stay focused.

Winter storytelling can deepen children’s connection to the changing seasons. Stories can frame nature walks or outdoor play – before heading outside, read a short winter tale. As you walk, look for signs from the story – frosted leaves, bird tracks or bare branches. After returning inside, revisit the story and invite children to retell it, adding what they saw outdoors.

Some ideas for linking nature to storytelling

• Hibernation tales alongside looking for places animals might rest.

• Migration stories paired with spotting birds in the playground.

• Snow and ice adventures connected to exploring frozen water in trays.

This reinforces vocabulary, observation skills and environmental awareness, while keeping the joy of the season alive.

The environment matters almost as much as the words. A cosy, inviting storytelling space can transform a simple reading into a magical event.

Consider:

• Soft blankets or rugs to sit on.

• Twinkling fairy lights or battery candles for a warm glow.

• A small basket of winter props: pinecones, faux snow, mittens or animal toys.

• A backdrop of winter scenery – even a printed photo or fabric with snow patterns.

By creating a distinct space, children recognise that storytelling is a special, shared moment.

As children become familiar with winter tales, invite them to take the storyteller’s seat. This might be retelling a favourite book with picture prompts, creating their own simple winter characters and adventures, or using puppets to act out a scene. Peer-to-peer storytelling not only builds confidence and communication skills, it also gives you an insight into how children are processing and re-imagining the stories they hear.

Winter storytelling in the early years is more than just seasonal fun – it’s a way to build language, foster imagination, celebrate culture and connect children to the natural rhythms of the year. By blending folklore, sensory props, movement and the magic of the outdoors, we can create experiences that warm the heart as much as any mug of hot chocolate!

So this season, gather the children close, let the fairy lights twinkle, and open the door to a winter of stories they’ll never forget.

Dukes Education Group run both Hove Village and Reflections Nursery and Forest School in Sussex.

To discuss opportunities at Hove Village please call 01273 037449 or visit www.hovevillage.com

To discuss opportunities at Reflections Nursery please call 01903 251518 or visit www.reflectionsnurseries.co.uk

Dukes Education Group run both Riverside Nursery Schools and The Kindergartens in Surrey/London.

To discuss opportunities at Riverside Nursery Schools please call 020 3475 0455 or visit www.riversidenurseryschools.com

To discuss opportunities at The Kindergartens please call 020 7326 8765 or visit www.thekindergartens.com

Dyslexic Thinkers) and This is Dyslexia (a book for adult Dyslexic Thinkers) – a new and revised edition was published in October 2024.

Dyslexic Thinkers) and This is Dyslexia (a book for adult Dyslexic Thinkers) – a new and revised edition was published in October 2024.

n’t feel they’re ready for yet, such as racism.

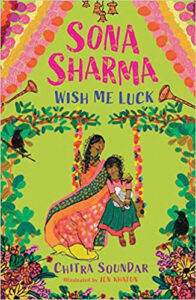

n’t feel they’re ready for yet, such as racism. king to create a book collection that truly reflects the rich ethnic diversity of our society, we might look to find authentic representation of as many different ethnicities as we can. Great choices for the littlest readers are the Lenny series, by Ken Wilson Max, the Zeki series by Anna McQuinn and Rosalind Beardshaw (both Alanna Max), and Bhorta Bhorta Baby by Jumana Rahman and Maryam Huq (Bok Bok Books). In picture books for three to seven year olds, we recommend Strong Like Me, by Kelechi Okafor and Michaela Dias-Hayes (Puffin), Esma Farouk, Lost in the Souk by Lisa Boersen, Hasna Elbaamrani and Annelies Vandenbosch (Floris Books), My Bollywood Dream by Avani Dwidevi (Walker Books), and Aisha’s Colours by Nabila Adani (Walker Books). Emerging independent readers will love the Sam Wu series by Katie and Kevin Tsang (Farshore), aged seven and above, the Sona Sharma series by Chitra Soundar (Walker), aged six and above, and the brand new Destiny Ink series by Adeola Sokunbi (Nosy Crow), aged five and above.

king to create a book collection that truly reflects the rich ethnic diversity of our society, we might look to find authentic representation of as many different ethnicities as we can. Great choices for the littlest readers are the Lenny series, by Ken Wilson Max, the Zeki series by Anna McQuinn and Rosalind Beardshaw (both Alanna Max), and Bhorta Bhorta Baby by Jumana Rahman and Maryam Huq (Bok Bok Books). In picture books for three to seven year olds, we recommend Strong Like Me, by Kelechi Okafor and Michaela Dias-Hayes (Puffin), Esma Farouk, Lost in the Souk by Lisa Boersen, Hasna Elbaamrani and Annelies Vandenbosch (Floris Books), My Bollywood Dream by Avani Dwidevi (Walker Books), and Aisha’s Colours by Nabila Adani (Walker Books). Emerging independent readers will love the Sam Wu series by Katie and Kevin Tsang (Farshore), aged seven and above, the Sona Sharma series by Chitra Soundar (Walker), aged six and above, and the brand new Destiny Ink series by Adeola Sokunbi (Nosy Crow), aged five and above.